At the dawn of the 21st century, we slowly and painfully create a globalized international environment, where technology and the energy that powers it become of paramount importance. Indeed, in the context of the Rio+20 Conference in June 2012, the UN Secretary-General referred to a new emerging human right of primordial importance: a right of access to energy, that would enable vulnerable populations to ac-quire access to information and technology and thus escape the vicious circle of exclusion, illiteracy and poverty.[1]

The Story So Far

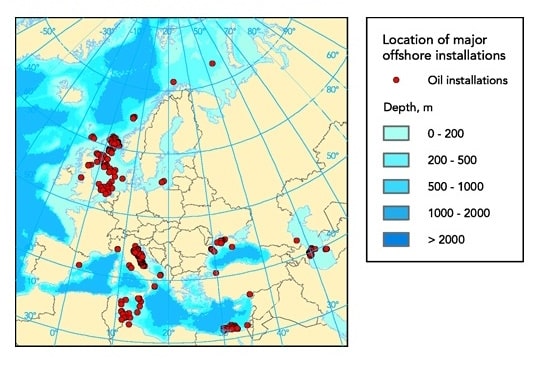

Europe does not have for the moment any major indigenous sources of energy. Any European oil and gas produced may be found offshore[2] in the maritime zones around the continent[3] firmly under the jurisdiction of the coastal States, which exercise full sovereignty in their territorial waters[4] and enjoy sovereign rights for the purposes of exploring and exploiting its natural resources in the continental shelf[5] and the Exclusive Economic Zone[6], once such is proclaimed. However, the environmental impact of any major accident could hardly be contained within coastal waters and could potentially develop into a major ecological and financial disaster, affecting the marine environment as a whole. The case of Deepwater Horizon, a $350 million offshore oil-drilling rig operating in the Gulf of Mexico, which blew up in April 2010 causing 11 deaths, a catastrophic oil spill of more than 4 million barrels affecting more than 1000km of coastline, grave damage to private property and fines and penalties to the industry in the neighbourhood of $40 billion[7], was the latest such example with catastrophic repercussions.

Major offshore installations in and around Europe

Source: European Environment Agency

In light of this experience the European Commission revisited in the months following that disaster the existing contingency plans – and it came to the conclusion that, in spite of the increasing importance of the offshore industry for the European economy as a whole, its regulation remains firmly in national hands and thus fragmented, with a wide diversity of rules and regulations on operation, accident prevention procedures, damage mitigation techniques and liability standards.[8] Truth be told, this is the case worldwide and not just in the European continent: the offshore industry has (successfully) resisted any attempt to create common standards and arrive at a globally binding regulatory regime[9] – and it appears that it continues to do so to this day.

The institutional and normative response of the European Commission included an offshore industry regulators’ forum[10] set to supervise and coordinate the enforcement of common standards for the offshore industry, as set out in a draft Regulation on safety of offshore oil and gas prospection, exploration and production activities.[11] On 21 February 2013 the European Parliament and the Council reached a political agreement to change the format of the proposed legislation to a Directive; the reformulated text is expected to be adopted by the European Parliament in the coming months. The news were greeted with some enthusiasm by parts of the industry,[12] which argued that a uniform regulation would somehow lower the existing national standards, while it clearly postpones the binding effect of the new rules for two more years after their final adoption.

A Comprehensive Regime at Last?

Be it as it may, the proposed legislation would provide the most extensive binding international regulation on the offshore industry. Albeit the product of a regional organisation, the Directive will cover offshore operations in areas far wider than the European Union States. It would regulate offshore installations to be found in the totality of EU waters, including the Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZ) and continental shelf in the Baltic Sea, the Northeast Atlantic Ocean (with the Greater North Sea, including the Danish Straits and the English Channel, the Celtic Sea, the Bay of Biscay and the Iberian coast, the waters around the Azores and Madeira and the Canary islands), the Mediterranean Sea and the Black Sea.[13] It would also affect offshore operations in Norway, Iceland and Lichtenstein, members of the European Economic Area (EEA), as well as in the parties to the Energy Community,[14] which includes Albania, Croatia, the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, Kosovo, Moldova and Ukraine with Turkey and Armenia as observers. In addition, the European Union has also decided to accede to the Madrid Protocol for the protection of the Mediterranean Sea against pollution resulting from exploration and exploitation of the continental shelf and the seabed and its subsoil,[15] thus bringing into a common umbrella the whole Mediterranean basin, including the States of its southern shores.

The proposed regime would cover the full spectrum of offshore operations, from placement and licensing of operations to decommissioning, including the transport of oil and gas through pipelines to another offshore installation, onshore processing or storage activity or on board ship for further transport. It is interesting to note that the new regulations would also apply to existing offshore installations and not only to new installations and operations, built after they come into force. In practice, this would entail a major review of existing operations in all European waters – and even beyond, as the stated will of all shareholders is to expand the common standards applicable in EU operations in all their operations worldwide. On the other hand, this ambitious expansion of the scope of application may not be as dramatic as it seems at first sight since the offshore industry is comprised of a limited number of major companies, which share the incentive to level their playing field.

There is, however, a gaping hole in this comprehensive approach: the draft Directive covers all offshore oil and gas installations but not, for the time being, offshore installations used for renewable power generation. It is worth considering in this respect that the European Union is committed to a very significant expansion of its renewable energy market, with the creation of major offshore wind farms and their related infrastructure;[16] as well as the possibility of developing an offshore carbon capture and storage (CCS) facilities to move carbon dioxide by pipeline to depleted gas fields in the North Sea.[17]

Pillars of regulation

The proposed legislation is built on the basis of the existing EU acquis and the applicable international instruments. The challenge in this respect is not so much the adoption of new rules to cover obvious gaps; it rather lies in its capacity to converge existing regulatory regimes and create therefrom synergies reinforcing the required outcome. In the following paragraphs, I will attempt to highlight some instances of these parallel regimes as they apply in practice before an offshore installation is placed in the marine environment, during the period of its productive operation and after a major polluting incident occurs.

Pillars of regulation I: Before

For oil and gas offshore installations the licensing principle is firmly established both in EU legislation and in the 1995 Mediterranean Offshore Protocol.[18] Technically, the proposed Directive will expand the provisions of Directive 1994/22 on the conditions for granting and using authorizations for the prospection, exploration and production of hydrocarbons.[19] Each stage of the offshore operations is subject to a separate license. With a view to grant any such license, the competent authority would be required to consider all relevant technical and financial risks in addition to a fully-fledged environmental impact assessment, as already required by customary law,[20] the 1991 UNECE Espoo Convention on Environmental Impact Assessment in a transboundary context[21] and the EIA Directive 85/337/EEC, as repeatedly amended.[22]

Particular attention is paid to the need for public participation in the course of the licensing process: draft article 5 requires that the public “shall be given early and effective opportunities to participate in [such] procedures”, due regard being given to safety and security considerations.[23] In effect, this provision reinforces the system created by Directive 2003/35 on public participation[24] and the 1998 UNECE Aarhus Convention on access to information, public participation in decision-making and access to justice in environmental matters.[25] It is worth noting in this respect that although the somewhat aged text of the Offshore Protocol does not expressly provide for participation of the public in the licensing process, also applicable is the much stronger obligation of article 14 of the 2008 Protocol on Integrated Coastal Zone Management,[26] which is the only binding instrument empowering citizens of the Mediterranean southern shores to have recourse to justice for environmental matters.[27]

Pillars of regulation II: During

The risk assessment exercise takes an even more comprehensive character in the proposed Directive in the form of the Major Hazard Report (MHR). This new environmental tool encompasses best technical and technology practices, best applicable standards in matters pertaining to health and safety at work, as best set out in Directive 89/391/EC on the introduction of measures to encourage improvements in the safety and health of workers at work[28] and its implementing 11th individual Directive 92/91/EEC concerning the minimum standards for improving the safety and health protection of workers in the mineral-extracting industries through drilling,[29] as well as contingency plans and emergency procedures in cases of accident.

These are probably the most important and at the same time the most controversial areas of the proposed legislation.

It is generally accepted that in order to properly assess the effectiveness of a major emergency risk, it is imperative to review all aspects of oil and gas production, including the design of offshore installations and their assorted infrastructure. Therein lies a major regulatory gap as the construction and equipment of offshore structures is not covered by the EU product safety legislation.[30] The only applicable international regulation is the IMO Code for the Construction and Equipment of Mobile Offshore Drilling Units (MODU),[31] which effectively views such offshore platforms as another type of vessel with no real relevance for operations carried out on them.

The same is true for emergency response: The EU Civil Protection Mechanism[32] and the European Maritime Safety Agency (EMSA), set up after the Erica incident, may be expanded to also cover offshore installations. EU accession to the 1994 Mediterranean Offshore Protocol would also allow the integration of the Regional Marine Pollution Emergency Response Centre (REMPEC) for the Mediterranean Sea in offshore emergency prevention, preparedness and response; no such global system exists although the IMO International Convention on Oil Pollution Preparedness, Response and Cooperation (OPRC)[33] does include the obligation of operators of offshore units under the jurisdiction of the parties are also required to have oil pollution emergency plans and coordinate their operation with national systems for responding promptly and effectively to oil pollution incidents.

Therein lies the sticky point: the role of national response systems and their obligation to supervise the system and coordinate emergency response. The industry has adopted over the years a number of emergency plans and has set up formal and informal coordination committees, primarily the Oil Spill Prevention and Response Advisory Group in the United Kingdom and the North Sea Offshore Authorities Forum (NSOAF), coordinating regional cooperation between the competent authorities. The proposed legislation requires that a national competent authority should be entrusted with the overall supervision of the system[34] coordinating transboundary action,[35] essentially through the EU Offshore Oil and Gas Authorities Group.[36]

The exact apportionment of responsibilities will no doubt be subject to further debate and compromise but it is already evident that the central idea is to create an independent authority with the primary goal to regulate “safety and environmental protection” while transferring “primary responsibility for control of major hazard risks” to another set of national authorities, all of which distinct from the authority competent to exercise “functions relating to [national] economic development, in particular licensing of offshore oil and gas activities, and policy for and collection of related revenues”.[37]

The creation of this decentralised system is designed to increase the transparency of the decision-making processes and public accountability. It attempts to internalise lessons learned by the US authorities in the aftermath of the Deepwater Horizon disaster, when the general supervision of the system was transferred to the Bureau of Oceans Energy Management, Regulation and Enforcement (BOEM) since it was felt that the Minerals Management Service was much more geared to revenue-producing licensing rather than the strict supervision and enforcement of environmental and labour standards of operation.[38] The question of efficiency is such a multi-level system of supervision, however, remains open.

Pillars of regulation III: After

The final element remains the horny issue of responsibility and liability for environmental damage. Although the global standard of liability remains vague,[39] the European Union has adopted a comprehensive system of environmental liability in Directive 2004/35[40], which, however, covers only the territorial and surface waters of the member States. It becomes evident, therefore, that an extension of the Environmental Liability Directive to coincide with the scope of application of the proposed instrument is elementary.

An additional line of reflection is the possibility of introducing a requirement for mandatory insurance. Article 14 of the Environmental Liability Directive requires States “to encourage the development of financial security instruments and markets by the appropriate economic and financial operators, including financial mechanisms in case of insolvency, with the aim of enabling operators to use financial guarantees to cover their responsibilities under this Directive”. Would that level of financial liability suffice for offshore operations? It is certainly the case that the offshore industry currently operates on a system of compulsory insurance on the basis of national legislation but it is clear that the full deployment of the EU system would also require a corresponding adjustment to the main instrument of environmental policy.

It is indicative of the trend that, in view of the existing gap in the EU liability toolbox, the European Court of Justice had easy recourse to another, more comprehensively regulated regime, that of waste. In the Commune de Mesquer case,[41] the ECJ felt secure in its decision to affirm that “hydrocarbons accidentally spilled at sea following a shipwreck, mixed with water and sediment and drifting along the coast of a Member State until being washed up on that coast, constitute waste within the meaning of Article 1(a) of Directive 75/442, where they are no longer capable of being exploited or marketed without prior processing”.[42] Although the Court correctly finds a proactive way to render judgment and address existing needs, it is evidently not sustainable to operate a liability regime in a high investment area[43] trusting the sound judgment of this or any other court or tribunal. Clearly, a well-defined framework is urgently needed.

Final remarks

The brief remarks in the previous paragraphs do not purport to conduct any thorough review of the proposed legislation nor to denigrate a commendable effort of comprehensive regulation is a fairly self-organised industry. They rather purport to highlight some areas of concern or simply identify areas where further reflection is required. For the time being, it is clear that the industry has successfully managed to slow down the regulatory process, acquire further scope for negotiation as to the contents of the proposed legislation and effectively put off any implementation well within the next few years – no doubt counting on the inevitable diversion of the required political will once easterly winds turn the weather bell to another direction.

ENDNOTES

- UN, Report of the UN Conference on Sustainable Development, Rio de Janeiro, 20-22 June 2012, UN Doc. A/CONF.216/16, paragraph 129. See also Adrian J. Bradbrook & Judith G. Gardam, Energy and poverty: A proposal to harness international law to advance universal access to modern energy services, 37 Netherlands ILR 2010, pp. 1-28.

- Strictly speaking, offshore installations may also be found in areas beyond national jurisdiction but the relevant technology remains experimental and expensive and the discussion of the applicable legal regime goes beyond the limited scope of the present paper.

- The European Commission indicates that “[t]he number of offshore installations in the North East Atlantic alone exceeds 1,000. Furthermore, while installations in the Black (Romania) and Baltic Seas still only amount to single digits, there are currently over 100 installations operating in EU waters in the Mediterranean (Italy) and plans to start new exploration are reported in the Maltese and Cypriot sectors. Oil and gas exploration or production also takes place in the close vicinity of the EU, off the coasts of Algeria, Croatia, Egypt, Israel, Libya, Tunisia, Turkey and Ukraine.”; Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament and the Council, Facing the challenge of the safety of offshore oil and gas activities, 12 October 2010, COM(2010) 560 final, p. 2. It appears that more than 90% of the oil and 60% of the gas produced in Europe comes from offshore sources.

- Article 2 of the 1982 UN Law of the Sea Convention (hereinafter: LOSC).

- Article 77 LOSC.

- Article 56 paragraph 1a LOSC, which covers ‘sovereign rights for the purpose of exploring and exploiting, conserving and managing the natural resources, whether living or non-living, of the waters superjacent to the seabed and of the seabed and its subsoil, and with regard to other activities for the economic exploitation and exploration of the zone, such as the production of energy from the water, currents and winds’.

- For an overview see the workings of the National Commission on the BP Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill and Offshore Drilling, available at http://www.oilspillcommission.gov. See also Aditi Mene, The Gulf of Mexico oil spill: Consequences for the oil and gas industry, http://uk.practicallaw.com/3-504-7901 (last visited: 25 March 2013); Marissa Smith, The Deepwater Horizon disaster: An examination of the spill’s impact on the gap in international regulation of oil pollution from fixed platforms, 25 Emory ILR 2011, pp. 1477-1516; Nicholas J. Lund & Niki L. Pace, Deepwater Horizon natural resource damages assessment: Where does the money go?, 16 Ocean & Coastal LJ 2011, pp. 327-353; R. Abeyratne, The Deepwater Horizon disaster – Some liability issues, 35 Tulane Maritime LJ 2010, pp. 125-152; Kyriaki Noussia, The BP oil spill – Environmental pollution liability and other legal ramifications, European Energy & Environmental LR – EEELR 2011, pp. 98-107.

- COM(2010) 560 final, supra note 2, p. 3.

- For an early discussion, see Maria Gavouneli, Pollution from offshore installations, Martinus Nijhoff 1995.

- Commission Decision 2012/07 of 19 January 2012 on setting-up of the European Union Offshore Oil and Gas Authorities Group, OJ C 18/8, 21 January 2012.

- Proposal for a Regulation on safety of offshore oil and gas prospection, exploration and production activities, 27 October 2011, COM(2011) 688 final.

- Out-law.com, Legal news and guidance from Pinsent Masons, available at http://www.out-law.com/en/articles/2013/february/oil-and-gas-industry-welcomes-provisional-deal-on-eu-offshore-installation-safety-rules/ (last visited: 25 March 2013).

- See also article 4 of Directive 2008/56/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 17 June 2008 establishing a framework for community action in the field of marine environmental policy (Marine Strategy Framework Directive), OJ L 164/19, 25 June 2008.

- Created by the Treaty establishing the Energy Community, concluded in Athens on 25 October 2005 and entered into force on 1 July 2006, OJ L 198/18, 20 July 2006; detailed information available on http://www.energy-community.org/portal/page/portal/ENC_HOME/ENERGY_COMMUNITY/Milestones (last visited: 25 March 2013).

- The Madrid Protocol was concluded on 14 October 1995 and entered into force on 24 March 2011; available at http://www.unepmap.org/ (last visited: 25 March 2013).

- Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions, Renewable energy: A major player in the European energy market, 6 June 2012, COM(2012) 271 final. See also Michelle Portman, Involving the public in the impact assessment of offshore renewable energy facilities, 33 Marine Policy 2009, pp. 332-338.

- M.M. Roggenkamp & A. Haan-Kamminga, CO2 transportation in the EU: Can the regulation of CO2 pipelines benefit from the experiences of the energy sector?, 9 OGEL 2011 = Ian Havercroft, Richard Macrory and Richard B. Stewart (eds.), Carbon Capture and Storage : Emerging Legal and Regulatory Issues, Hart 2011, pp. 107-122; Monica Bergsten, Environmental liability regarding carbon capture and storage (CCS) operations in the EU, EEELR 2011, pp. 108-115.

- Articles 4-6 of the Offshore Protocol.

- Directive 1994/22/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 30 May 1994 on the conditions for granting and using authorizations for the prospection, exploration and production of hydrocarbons, as amended, OJ L 164/19, 25 June 2008.

- ICJ, Case concerning Pulp Mills on the River Uruguay, Argentina v. Uruguay, Judgment of 20 April 2010, paragraph 204, available at http://www.icj-cij.org/; see also Ilias Plakokefalos, ICJ, The Pulp Mills case, 26 TIJMCL 2011, pp. 169-183.

- The Convention was adopted on 25 February 1991 and entered into force on 10 September 1997, text available at http://www.unece.org/. The European Union is a party.

- Council Directive of 27 June 1985 on the assessment of the effects of certain public and private projects on the environment, as amended by Council Directive 97/11/EC of 3 March 1997, Directive 2003/35/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 26 May 2003 and Directive 2009/31/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 23 April 2009, as consolidated, 25 June 2009.

- Draft article 5 paragraph 3.

- Directive 2003/35/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 26 May 2003 providing for public participation in respect of the drawing up of certain plans and programmes relating to the environment and amending with regard to public participation and access to justice Council Directives 85/337/EEC and 96/61/EC, OJ L 156/17, 25 June 2003.

- The Convention was concluded on 25 June 1998 and entered into force on 30 October 2001, text available at http://www.unece.org/. The European Union is a party. See also Maria Gavouneli, Citizens envi-ronmental rights: The example of the Aarhus Convention, in Aliki Yotopoulos-Marangopoulos, Antonis Bredimas & L.-A. Sicilianos (eds.), Protection of the environment in law and practice, Athens 2008, pp. 125-154 [in Greek].

- Adopted on 21 January 2008 in Madrid, it entered into force on 24 March 2011; for the full text see http://www.unepmap.org. The European Union is also party to the Protocol.

- I have argued thus in Maria Gavouneli, Mediterranean challenges: Between old problems and new solutions, 23 TIJMCL 2008, pp. 477-497, at pp. 484-485.

- Council Directive 89/391/EC of 12 June 1989 on the introduction of measures to encourage improvements in the safety and health of workers at work, OJ L 183/1, 29 June 1989.

- Council Directive 92/91/EEC of 3 November 1992 concerning the minimum requirements for improving the safety and health protection of workers in the mineral-extracting industries through drilling, OJ L 348/9, 28 November 1992.

- Minimum requirements in relation to mobile non-production installations are met by Regulation (EC) 391/2009 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 23 April 2009 on common rules and standards for ship inspections and survey organisations (recast), OJ L 131/11, 28 May 2009; and Directive 2009/15/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 23 April 2009 on common rules and standards for ship inspection and survey organisations and for the relevant activities of maritime administrations, OJ L131/47, 28 May 2009.

- The 2009 MODU Code was adopted by IMO resolution A.1023(26) in 2009 and constitutes a thor-ough revision of the 1989 MODU Code adopted by resolution A.649(16). It applies to offshore units constructed after 1 January 2012.

- Council Decision 2007/779/EC, Euratom of 8 November 2007 establishing a Community Civil Protection Mechanism (recast), OJ L 314/9, 1 December 2007.

- Article 3(2) OPRC; the Convention was adopted on 30 November 1990 and entered into force on 13 May 1995.

- Draft article 8.

- Draft articles 17, 27 and 28.

- Supra note 10.

- Draft article 19.

- Mene, supra note 7, p. 10.

- The standard for ships is the IMO International Convention on Civil Liability for Oil Pollution Damage (CLC), adopted on 29 November 1969 and entered into force on 19 June 1975, as substantially amended by a Protocol adopted on 27 November 1992 and entered into force on 30 May 1996.

- Directive 2004/35/CE of the European Parliament and of the Council of 21 April 2004 on environmental liability with regard to the prevention and remedying of environmental damage, OJ L 143/56, 30 April 2004.

- ECJ, Case C-188/07, Commune de Mesquer v. Total France SA and Total International Ltd, Judgment of 24 June 2008.

- Supra, paragraph 63. See also Nicolas de Sadeleer, Liability for Oil Pollution Damage versus Liability for Waste Management: The Polluter Pays Principle at the Rescue of the Victims: Case C-188/07, Commune de Mesquer v Total France SA [2008] 3 CMLR 16, [2009] EnvLR 9, 21 JEL 2009, 299-307; Richard Caddell, Expanding the ambit of liability for oil pollution damage from tankers: The Charter-er’s Position Under EU Law: Commune de Mesquer v Total France SA and Total International Ltd, European Court of Justice, Case C-188/07, 15 JIML 2009, pp. 219-223.

- Seline Trevisanut, Foreign Investments in the Offshore Energy Industry: Investment Protection v. Energy Security v. Protection of the Marine Environment, in F. Seatzu, T. Treves, S. Trevisanut (eds), Foreign Investment, International Law and Common Concerns, Routledge, Oxford, 2013 (forthcoming, on file with the author).

About the author

Maria Gavouneli

Assistant Professor of International Law, National & Kapodistrian University of Athens, Greece